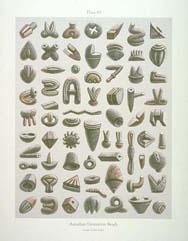

ABOUT THE FOUNDER: EVERITT ORMSBY HOKES Athough most accounts of Victorian England tend to omit the life of Everitt Ormsby Hokes, despite the fact that as both an artist and a scholar he was a paradigm of British cultural imperial values. Although chronologically one might consider him to be proto-post-Victorian, Hokes ranks as one of the more noteworthy personalities of the turn of the century. Born in 1864, the second son of Philip Hokes, a headmaster at the Reading School for Boys, Everitt Ormsby Hokes was not without intellectual or cultural stimulation. A voracious reader at an early age, he took to the novels of Robert Louis Stephenson, the travel accounts of Sir. Richard Burton, the archaeological discoveries of Sir. Austin Henry Layard, and, of course, the journals of Captain Lemeul Gulliver. Hokes envisioned himself similarly disposed to world travels, and at the age of eleven, demonstrated a natural talent for artistic invention by creating an encyclopediac account of an imaginary North African culture. As a result of his artistic aptitude, Hokes was awarded a scholarship to attend the London Academy of Fine Art where he studied paint ing and graphics and played on the academy's polo team. As Philip Hokes had limited financial resources to support his son's education, Everitt often had to resort to taking odd jobs such as being a street musician. Since Hokes did not have the financial means to go on a Grand Tour of Europe like some of his classmates, he tended to fulfill these desires vicariously by collecting the lithographs of David Roberts and similar artists working in the tradition of the picturesque images which were flooding London book shops and print dealers at that time. Following his certification from the London Academy of Fine Arts in 1891, Hokes secured employment in the noted publishing firm of John Murray and Sons, where he became an accomplished lithographic draftsman. For nine years Everitt Ormsby Hokes moved up through the artistic ranks of the firm, having demonstrated an ability to master a range of subjects and techniques. His work was highly praised in Henry Plomer's, A Short History of English Printing. While his reputation as an artist was valued by the Murray family, Hokes had the tendency to embellish details with subtle personal eccentricities which tended to go unnoticed until the plates had been printed and bound. While these liberties tended to be forgiven, the public scandal surrounding his overt inclusion of erotic imagery in the foreground of Plate 72 from Harrison's 100 Views of Punjia resulted in his dismissal. Although some have denied that the scandal surrounding Plate 72 had any effect on Hokes' father, three weeks after the scandal erupted, Philip Hokes died. While the death of his father was a great person loss, it also resulted in a much needed financial gain for Everitt. Using his inheritance, he was able to acquire a lithographic press and a collection of printing stones to start his own publishing firm in 1901. As proprietor of Hokes Scholarly Lithography, Everitt Ormsby Hokes published numerous scient ific manuscripts covering subjects ranging from entomology to archaeology. Through his publishing work and enthusiasm for archaeology, Hokes amassed a handsome collection of antiquities. The Hokes Archives, as it has since come to be called, might be thought of as a kunstkammer (from the German word meaning "art cabinet"). Like any museum or archive, the kunstkammer has been considered an essential apparatus of the learned person since the sixteenth century. Against this perspective of some four centuries of museum history, the Hokes Archives is unusual due to its singular emphasis on rare cultures. Some of the more important aspects of the collection include the Aazudians excavated in Iraq in the 1920's the Aazudiological Society of America and the Apasht excavated in the Hindoo Kush mountains of Afghanistan by the Delegation Archeologique. He also contrubuted significant work in the field of medical illustration. Hokes was also known for extensive contributions to medical illustration. An import exhibition of anatomical prints and drawings from the archives is now avialable for bookings. Working with James Randolph Denton of Philadephia, Pennslvania, Hokes published Rare Zoological Specimens and Ornithological Quadrupeds for the Association for Creative Zoology, which sought to counter the Theory of Evolution by adbocating for animal hybridy as the cause for species diversity. Hokes also published colorful circus posters for Circus Orbis, a small regional circus based in Jacksboro, Tennessee. Hokes' publishing efforts continued until 1939, when he died of a ruptured aneurysm. The business and the archives were entrusted to his only son Richard, who did not share his father's enthusiasm for archaeology. Within six months he moved to the United States after selling the printing firm to a company that produced sentimental greeting cards and advertisements for companies such as Mephisto Cigars. In 1978 Dr. Beauvais Lyons was able to acquire the archives at an auction of unclaimed goods from a storage locker in Portsmouth, Rhode Island. While little is known about the archives during the intervening years, it is generally assumed that Richard Hokes placed the collection in storage in accordance with his father's will. Since 1978 the archives has gone through extensive restoration and augmentation. In conclusion, it would be appropriate to note that Hokes had some rather unusual and often disputed theories regarding the nature of history and the study of archaeology. Though he never published his theories, he recorded many of his ideas in correspon dence with his elder brother Philip. I would like to close with an excerpt from one of these letters which was cited in Volume 12 of the Cheekwood Monograph Series: "It would seem that an act of faith is made by those who assume that science is an objective endeavor leading to an accurate understanding of a given subject. This problem is most apparent in the study of cultures, particularly those of the distant past. I would assert that history is a version of memory, and as such, is always selective, emphasizing one particular feature over another. One might conclude that the historian contributes most to our understanding not through the accuracy of his methods, but through the formation of our interpretations. It matters little whether these cultures really existed, for in the final analysis, they only persist in our imagination." POSTSCRIPT: Everitt Ormsby Hokes has an interesting connection to Knoxville through his uncle Cassius Demetrius Hokes (1848-1915), a painter, lithographer and self styled "professional prognosticator." Cassius D. Hokes operated a small printing shop on State Street in Knoxville during the last two decades of the 19th century. Between 1891 and 1897 he issued a series of lithographs which purported to show the appearance of familiar views in the Knoxville area at a distant future time. In 1894, in connection with the 100th anniversary of the University of Tennessee, Cassius D. Hokes produced the "Bicentennial View," in which he depicted the campus as it would appear in 1994, one hundred years in the future. The print enjoyed a moderate sale during the centennial celebration, but was regarded by many as an amusing and fanciful novelty and was soon forgotten. One of these prints is currently in the collection of the National Museum of American Art in Washington, DC.

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||