Academic Evolution and Hybridization: The Sciences and the Arts

An Interdisciplinary Symposium

Abstracts

Models and Fictions in Science

Science spends a lot of time discussing entities and systems that are known to be fictions - infinite populations, perfectly rational agents, and the like. In which ways are these things similar to the fictions of literature, and in which ways are they different? To what extent can we see the same faculties of human imagination at work in these two areas?

___________________________________________________________

Observational Networks in Science and the Arts

The boundary between science and art, as roughly coterminous with the

boundary between explanation and understanding or observation and

hermeneutic interpretation, is seen not as a difference between

activities that correspond to essentially distinct natural kinds, but

rather as properties of systems of observation that vary along a

continuum. Adopting the sociological perspective of second-order

observation, that is, observing how and under what conditions different

networks observe what they observe, dis-solves in practice many of the

enigmas that result from philosophy's essentialist demands for universal

explanations in principle. Drawing on the second-order cybernetics of

Heinz von Foerster, the systems theoretical perspective of Niklas

Luhmann, and more recently, Stephan Fuchs's comparative sociology of the

observer, I attempt to show how passive objects and expressive subjects

are not essentially different ontological domains, but instead are the

outcomes different kinds of observational net-works. A possible

limitation of this approach is discussed in relation to the homological

relationship between dreams and mathematics as discussed by Gregory

Bateson. Back to program

___________________________________________________________

Beyond Fragmentation: Complexity and Contradictions in the Natural and Social Sciences

In "Complexities. Why We Are Only Beginning to Understand the World," a

book published in 2008 in German by Sandra Mitchell, an American

philosopher and historian of science, puts forth the thesis that

priorities that have guided progress in the natural and social sciences

have been in conflict with the nature both of particular phenomena

studied, and of the world as a whole. Rather than searching for

simple, timeless and universal laws as the ultimate purpose of

scientific research, we should endeavor to aspire to compatibility

between the actual nature of the world, and our approaches to studying

it. In concrete terms, Mitchell contends that in one, exceedingly

important regard, the discrepancy between the concrete character of

phenomena to be studied, and established strategies for and notions of

research, is especially conspicuous. While all objects of study in the

natural and social world are both components and the result of complex

processes and conditions, theories and methods that orient research have

not been sufficiently conducive to capturing the complexity of reality

and any of its components. In effect, "science" describes efforts to

relate to reality in ways that appear to make it manageable, without

making sure whether relevant dimensions of reality truly can be made

manageable, and that they indeed are becoming manageable. Recognizing

the centrality of complexity to most-if not to all-research endeavors,

is the necessary precondition for taking actual steps toward

understanding the world. One of the key considerations in the endeavor

to do justice to the complexity of modern societies is reflection upon

its dynamic nature. An additional consideration, which Mitchell does

not address, is whether it is conceivable that researchers will be able

to tackle effectively issues of complexity without including in their

perspective the fact that modern societies are fraught with

contradictions of paradoxes.Back to program

___________________________________________________________

Toward an Integrative Understanding of Science

Science and the arts surely are distinct, but I will argue that

C. P. Snow's division of the two cultures is founded not on a deep

understanding of these domains but on a superficial set of differences.

By turning toward the central cognitive-imaginative act of scientist and

artist, we can locate the common core of these enterprises. Moreover, we

come to appreciate the conditions and practices that lead to becoming an

artist or scientist, which transcend particular knowledge and skills but

which are essential to the actual practice of creative art and original

science. By attending to this axial dimension of genuine art and

science, we uncover the genius in each and also an oft overlooked

pedagogical principle. Back to program

___________________________________________________________

The Natural History of Narrative:

The Neuropsychology of Belief

“Truth” it has been said is a “ripple on the ocean of reality.” We test our experiences (including thought) and behave as though we believe they are "true" to the extent that we have confidence in their validity. Two complementary cerebral processes ordinarily work in lockstep to provide us with more-or-less confidence in our experiences and the strength of ensuing beliefs: These processes involve an estimation of correspondence and coherence. “Correspondence” involves “reality-testing,” an empirical validation of an experience in the world. “Coherence” involves “theorizing,” a contextual validation derived from a narrative in which a new experience is more-or-less related to ongoing parallel and collateral experiences, as well as all those preceding. In large measure, these processes are lateralized in the brain. As information moves through us from sense organ to action system it is vulnerable to an assortment of problems, some of which are serious enough to require the attention of clinicians. Ordinarily, these processes are more-or-less balanced, but asymmetry in neuro-activation in concert with our gifts for resolving cognitive dissonance and making virtues of necessities, determine our "personality" and world view. The biological significance of “truth” and "belief" will be reviewed from the integrative perspective of ethology. Back to program

___________________________________________________________

Literature and Evolution: Joseph Carrol's Contributions as Seen by a Scientist.

Joseph Carroll was perhaps the first person to develop a sustained treatment of literary criticism from a Darwinian perspective in his 1995 book Evolution and Literary Theory. Since then he has steadily revised and expanded his perspective and is clearly a leader in this growing subfield of literary analysis. The journal Style recently published a lengthy new article by Carroll on a proposal for a comprehensive paradigmatic and methodological approach. In the process he critiqued the status of the area. Carroll's latest views will be summarized and then critiques of his proposals, including my own, and Carroll's response will be outlined.

___________________________________________________________

Blind Variation and Inspiration in the Creative Process

What is the source of creative inspiration in the arts and sciences?

Some, such as Simonton, have argued that it arises from blind variation,

and thus provides the raw material for evolution in the general sense,

which Campbell defined as "blind variation and selective retention."

However, complex systems theory, evolutionary biology, evolutionary

psychology, and depth psychology all point towards a more informative

explanation of inspired creativity, that is, of those creative

achievements that have a transformative and fruitful effect on artistic or

scientific culture. These insights have implications for both the

understanding and the enhancement of human creativity.

Back to program

___________________________________________________________

Heads and Tales

Why do humans spend so much time in concocting and consuming stories: why have we evolved into a storytelling species? What implications does understanding storytelling as a natural human behavior have for literary theory and for literary criticism? And how can studying literature help science probe human minds and behavior past and present?Back to program

___________________________________________________________

Symmetry as Science: H.G. Wells’ Evolutionary Narratives

University of Tennessee

acaleb@utk.edu

The recent increase in Darwinian readings of Victorian texts has lead to a reconsideration of the relationship between science and literature. The works of Gillian Beer and Bernard Lightman has forced literary scholars—particularly those concerned with the nineteenth century—to reassess works of fiction as cultural artifacts of the popularization of science. Moreover, the recent work of Joseph Carroll and Brian Boyd has suggested that literature does not merely draw upon scientific facts to illuminate the content, but rather mimics the structures of evolutionary thinking in the narrative form.

Continuing with this line of inquiry, I am interested in reconsidering H.G. Wells’ 1890s scientific romances in regards to their evolutionary narrative structures. Drawing upon the works of both Darwin and Huxley, Wells uses an evolutionary circling effect in works such as The Time Machine (1895) and The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896) as a means of both narrative progression and social commentary. By establishing a pattern of symmetry throughout the novels and demonstrating unity through variety, Wells reflects Huxley’s aesthetic view of the inseparability of the scientist and artist, an important Victorian notion that was lost for the vast majority of the twentieth century. Through Wells’ works, we can see how a trained scientist and professional writer merges these seemingly contrasting disciplines into a unified evolutionary narrative.Back to program

___________________________________________________________

The Circulation of Concepts

A major obstacle to chemistry being a deductive science is that its core concepts very often are defined in circular manner: it is impossible to explain what an acid is without reference to the complementary concept of a base. There are many such dual pairs among the core concepts of chemistry. Such circulation of concepts, rather than an infirmity chemistry is beset with, is seen as a source of vitality and dynamism.Back to program

___________________________________________________________

The Humanities and Sciences through the Eyes of Two of Its Eminent Practitioners: Jacques Barzun and E. O. Wilson

When universities came into existence in medieval Europe, their curricula were very small, with theology being the primary focus. Through the intervening centuries curricula expanded slowly at first and rapidly in the last century or two. A university today may have dozens of departments, each of which may be subdivided into numerous divisions. Chemistry, for example, is typically divided into four to six divisions, with a member of a division often hardly conversant with the scholarly interests of other members of the same division, let alone with the interests of members of the other divisions. Fragmentation rules the day. What negates this entropy is clearly teaching, learning, research, scholarly publication, and public service. Are there more subtle ways by which the disciplines, particularly in the humanities, fine arts, social sciences, and “hard” sciences, are united?

This talk will explore this question by examining the views of two eminent academics: the Columbia University historian Jacques Barzun, who is still publishing at the age of 100, and the Harvard University entomologist E. O. Wilson, whose range of interests is breathtaking. Both men are intelligent, opinionated and persuasive individuals, with diametrically opposed views on the question I raised above. I will examine their views in light of two of their well-known and controversial books: Barzun’s Science: The Glorious Entertainment, published in 1964, and Wilson’s Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge, published a decade ago. Barzun, who dislikes science for a number of reasons, believes that the physical and biological sciences have won the cultural wars, even though the author believes that many disciplines in the humanities to be intellectually superior to those in the sciences. Wilson, on the other hand, looks for ways including the reductive method of science to unify all knowledge. Back to program

___________________________________________________________

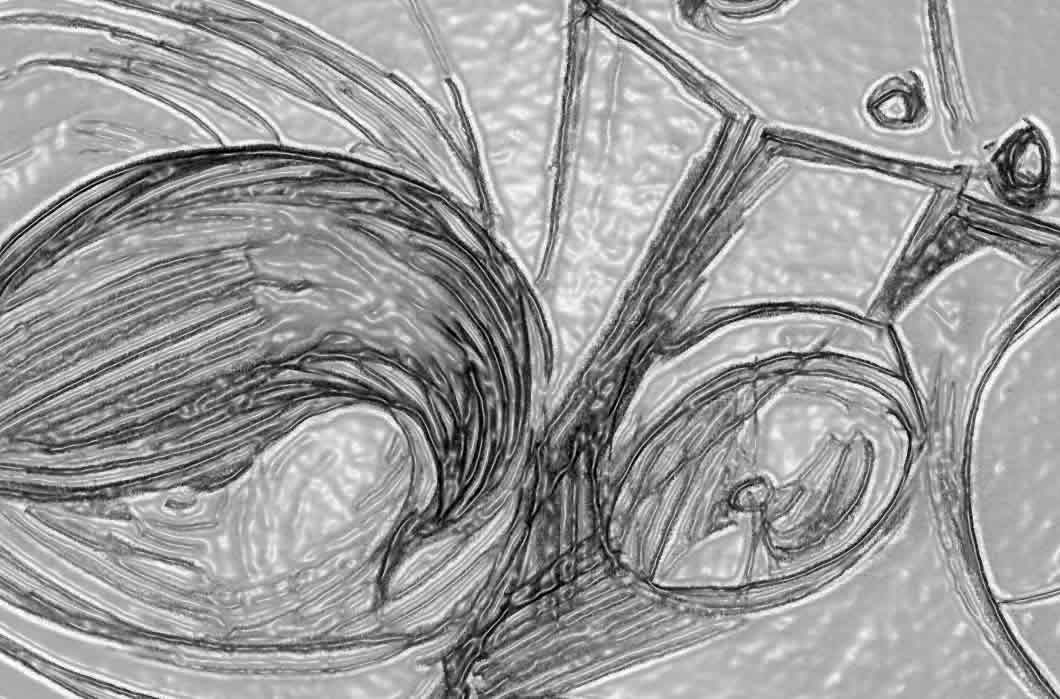

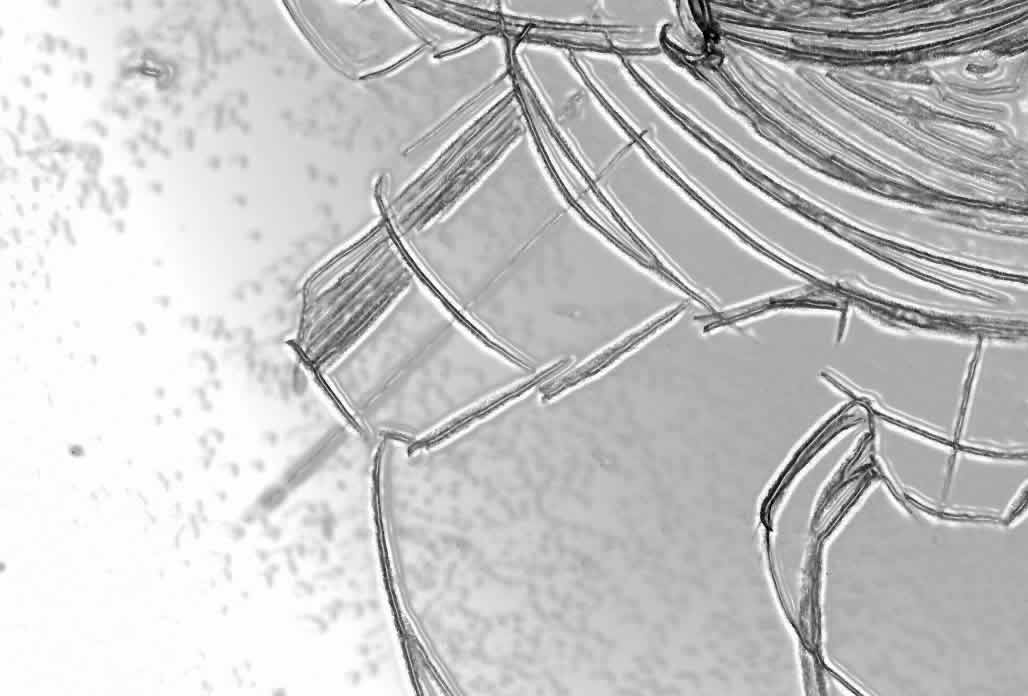

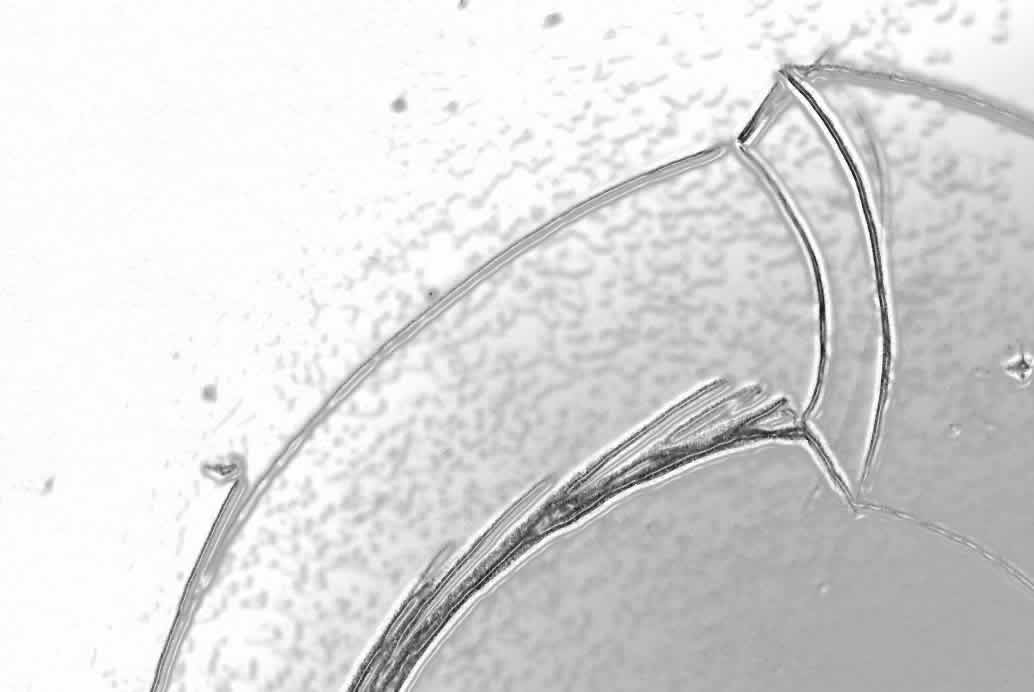

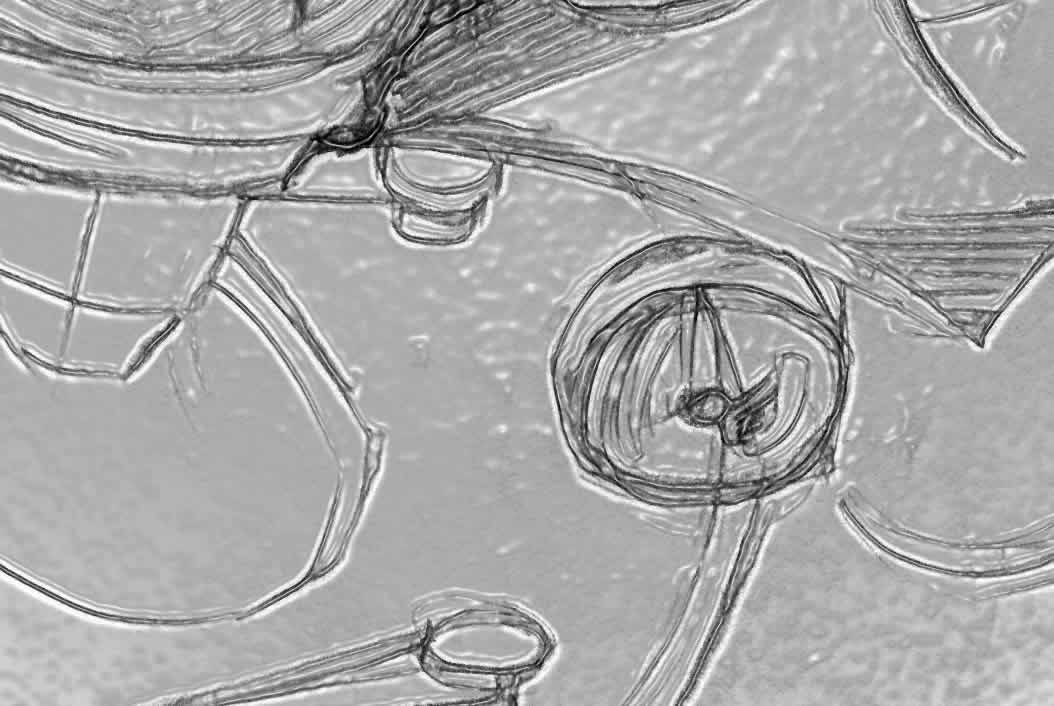

The Zoological label as literary form

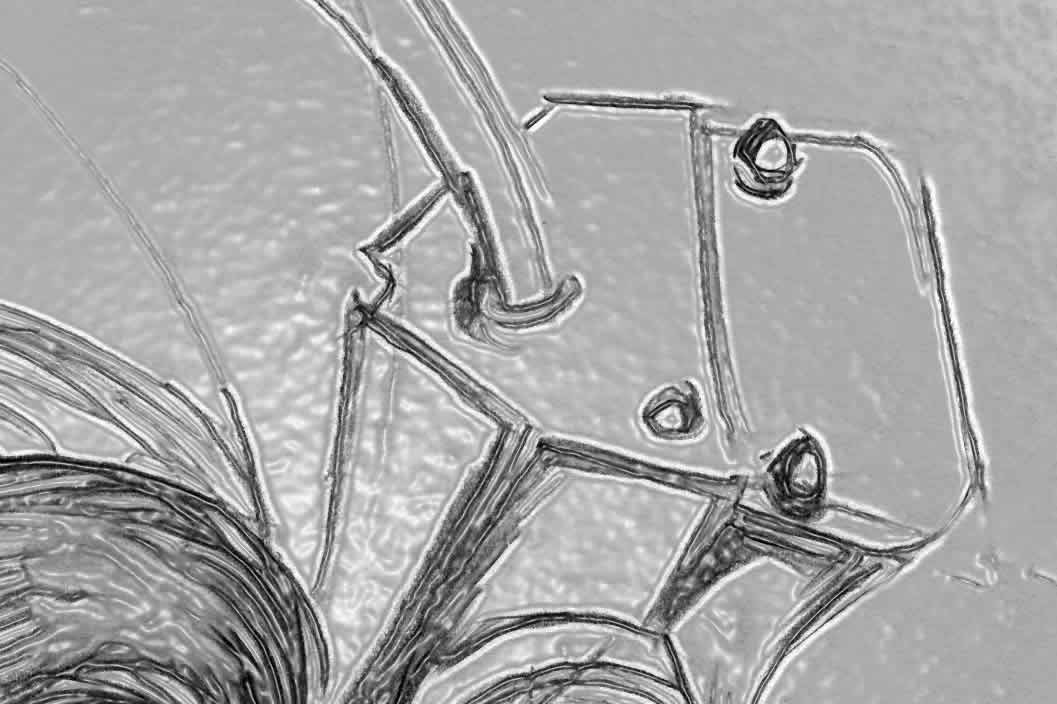

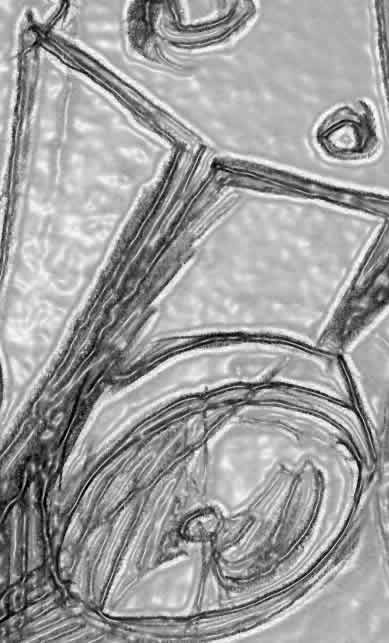

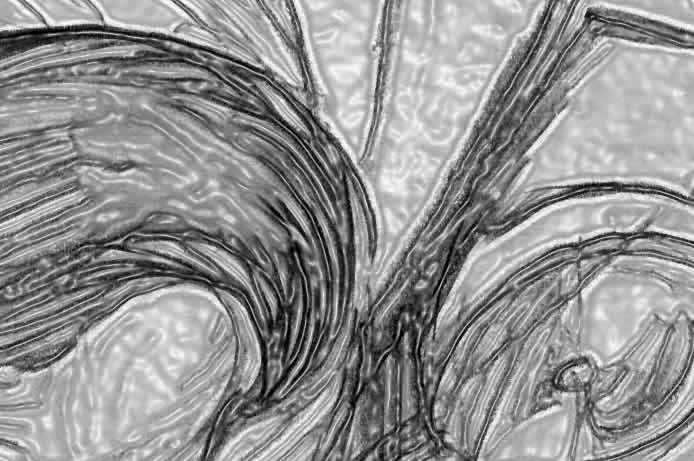

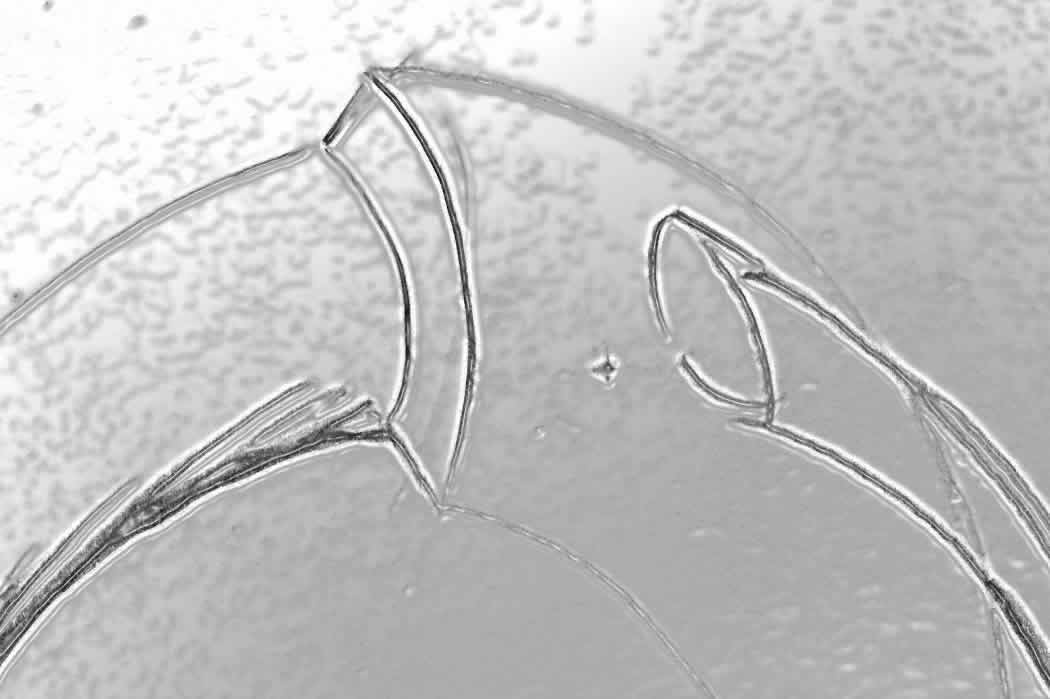

A Zoological label's precision, brevity, and authority (collector, identifier, author), its geographic and taxonomic attention, in my opinion, provided Vladimir Nabokov with a unique literary source of inspiration. The label's requirement of a precise spatial locality must have inspired and honed Nabokov's biogeography: the distribution of life, an amalgam of labels. A naturalist remembers geographic localities as labels, to which memory pins a species' name. This name is in Latin, still a universal tongue, and needs no translation.